What is Brugada Syndrome?

Brugada syndrome is a genetically determined arrhythmic syndrome that predisposes to the development of even serious heart rhythm disorders, which can cause sudden death .

The arrhythmic events of the disease usually occur at night , a characteristic for which this pathology is called by different names in various Asian regions: “Lai Tai” (death during sleep) in Thailand, “Bangungut” (scream followed by sudden death during sleep) in the Philippines, “Pokkuri” (sudden and unexpected death during the night) in Japan.

Brugada syndrome owes its name to two Spanish cardiologist brothers, Pedro and Josep Brugada , who fully described it in 1992.

However, already in the 1980s, Italian cardiologists Nava, Martini and Thiene outlined its main characteristics in the Italian Journal of Cardiology.

How common is Brugada Syndrome?

Brugada syndrome is a rare condition: according to reliable estimates, in fact, 1 to 30 people out of every 10,000 individuals considered are affected by it.

The greatest diffusion occurs among populations of Asian origin , in particular among people of Thai and Lao origin . According to the medical literature on the subject, Brugada Syndrome would be the cause of 4-12% of all cases of sudden cardiac death and of more than 20% of all cases of sudden cardiac death in people with a structurally healthy heart.

What are the causes of Brugada Syndrome?

Brugada Syndrome is a disease caused by genetic alterations and is transmitted from one generation to the next in a so-called autosomal dominant manner . autosomica dominante.

This means that it is sufficient for just one parent to have an abnormality in an altered gene for them to transmit the disease to their offspring.

In about 40% of cases, the genetic anomaly can be determined by finding a specific alteration in a gene. To date, 18 different genetic anomalies are known that can cause the disease. These anomalies produce an electrical defect in the ion channels that determine the conduction of the impulse on the membranes of cardiac cells. From this defect, the electrical activity of the heart can undergo sudden alterations that cause arrhythmias that are sometimes fatal. The gene most frequently involved is SCNA5A , which codes for a subunit of a channel that allows the passage of sodium ions through the membrane of the cardiac cell.

In 60% of cases we are still unable to determine the precise mechanism that determines the disease, whether it is genetic or otherwise.

How does Brugada Syndrome manifest itself?

Most patients with Brugada syndrome remain asymptomatic (70%).

In approximately 30% of cases, patients show symptoms of variable severity that occur more frequently in young males (with a male/female ratio of 8:1) between the ages of 30 and 40. However, cases in a very broad age range (6-77 years) have been described in literature.

Symptoms may include palpitations, blurred vision, sudden dizziness, fainting, or tightness in the chest.

The cardinal symptom in patients with Brugada Syndrome is sudden loss of consciousness or syncope. Arrhythmic syncope is typically sudden, not preceded by warning symptoms, unlike the non-arrhythmic so-called vagal or neurally mediated syncope that occurs after a series of warning symptoms, also frequent in patients with Brugada.

Sudden death, although rare, represents, in 5% of cases, the first (and last) symptom of the disease without any warning signs.

Symptoms almost never occur during exercise, but in most cases at rest, after exercise, during digestion, at night, since the slowing of the heart rate and the increased vagal tone are factors that favor the genesis of the arrhythmias that are the basis of the symptoms.

In the most dramatic cases, the so-called arrhythmic storm may occur, which consists of a succession of ventricular arrhythmias that lead to fainting or actual cardiac arrests that require urgent resuscitation and electrical stabilization interventions.

How is Brugada Syndrome diagnosed?

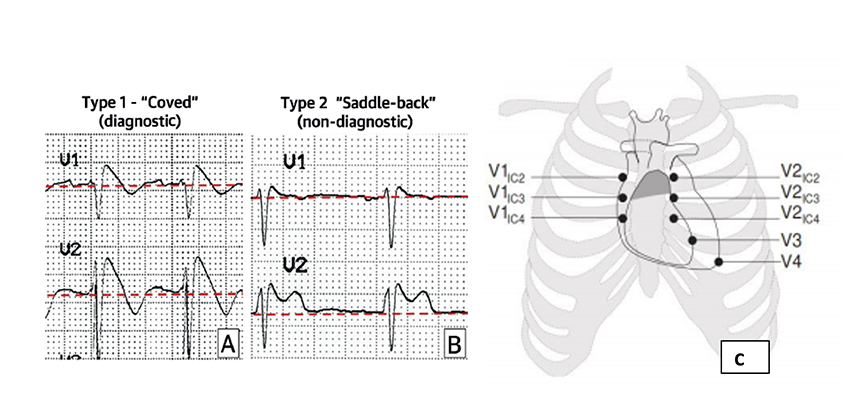

The diagnosis of Brugada syndrome is made with the electrocardiogram . Affected patients present alterations that are localized in a narrow area of cardiac tissue located on the external surface of the infundibulum of the right ventricle below the epicardium. The effects of this alteration can be recorded by the electrocardiogram, in particular by the electrodes that are positioned in the II°-III°-IV° intercostal space, just above the diseased area (fig 1).

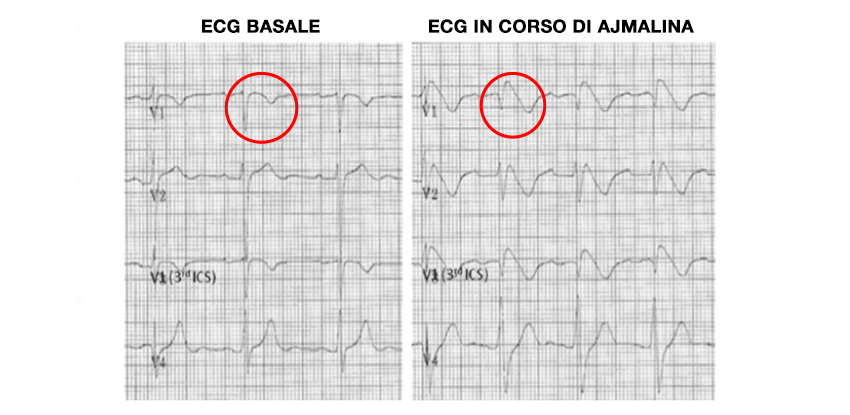

When the alteration is evident, we speak of a Brugada pattern TYPE 1 : the recording of this pattern allows us to make a certain diagnosis of the syndrome. The recording of type 2 and type 3 patterns only raises the suspicion of the presence of the syndrome, which must be confirmed by provocative tests: ajmaline tests (infusion of ajmaline or flecainide) which reveal the TYPE 1 pattern in affected subjects (fig 2). In fact, the TYPE 1 pattern can be intermittent: when it is present, it indicates an active anomalous electrical current which can give rise to short circuit phenomena that trigger arrhythmias.

Per effettuare DIAGNOSI CERTA è necessario registrare il pattern TIPO 1To make a CERTAIN DIAGNOSIS it is necessary to record the TYPE 1 pattern (fig. 1) spontaneously if present or by making it emerge with provocative tests.

How is arrhythmic risk assessed in Brugada Syndrome?

The risk of developing arrhythmic events in affected patients is highly variable.

The presence of a sudden palpitations, a sensation of blurred vision, dizziness are signs of interest on the part of the cardiologist as they are possible markers of brief arrhythmias and therefore of risk.

Familiarity with sudden death at an early age in first-degree relatives significantly increases the arrhythmic risk.

While less certain data exist for higher-ranking relatives or for events at an advanced age.

Syncope (fainting out of the blue), the recording of complex major ventricular arrhythmias and finally aborted cardiac arrest are considered important risk factors for sudden death. In patients with syncope episodes , events related to benign phenomena of lowering of blood pressure and frequency linked to vagal reflexes (neurally mediated syncope) must be excluded, which have no significant prognostic impact. Patients with syncope episodes out of the blue, on the other hand, show a risk of serious events per year of approximately 2%.

Patients surviving cardiac arrest have an 8% annual risk of recurrence and are the highest risk subgroup.

The complete absence of symptoms is reassuring, although sometimes serious adverse events can occur in subjects who have never shown warning signs. This group of patients represents the greatest challenge for the cardiologist in assessing risk.

The presence of the type 1 pattern on the ECG can be helpful in this evaluation: if it is present spontaneously without the need to induce it with provocative tests, the arrhythmic risk is higher because it indicates the active presence of the anomalous electrical current. This subgroup of patients has a risk of sudden death of 1-2% per year. It is therefore necessary to look for the spontaneous emergence of the TYPE 1 pattern with a 12-lead Holter recording over 24 hours and not limit oneself to the recording of a single electrocardiogram.

If the Type 1 pattern never occurs spontaneously, the arrhythmic risk is low. This reassuring data must however be confirmed with repeated holter monitoring over time to exclude an unfavorable evolution of the risk. holter ripetuti nel tempo per escludere una evoluzione sfavorevole del rischio.

Always in patients at intermediate risk, the stratification of the arrhythmic risk can also make use of the electrophysiological study. This test consists in the stimulation of the right ventricle (defined as programmed) by means of impulses capable of evoking anomalous arrhythmic responses in patients with particular electrical vulnerability . Such vulnerability, if present, constitutes a further important indicator of arrhythmic risk in patients affected by Brugada Syndrome.

The clinician also uses, in the overall risk assessment, other elements such as the concomitant presence of atrial fibrillation, sinus node disease, the presence of widened, fragmented QRS complexes on the ECG, early repolarization, atrioventricular block.

On the basis of all the above elements, the cardiologist formulates an individualized risk assessment for the individual patient and orients himself towards the most appropriate form of treatment.

What Are the Treatments for Brugada Syndrome?

Le terapie più avanzate per la Sindrome di Brugada, dall’impianto di defibrillatore all’ablazione epicardica.