Extrasystoles are heartbeats that occur earlier than expected during cardiac activity, temporarily interrupting its usual rhythm.

In physiological conditions, the heart is activated by specific cells of the activation and conduction tissue that generate and transmit the impulse of each single beat to the entire heart. The other cells are passively activated and give rise to the contraction of the cardiac muscle. When instead “anarchic” cells autonomously generate electrical impulses outside the physiological activation cycle, an extrasystole occurs. The patient who is affected feels a sensation described as a blow, a dip in the chest, a feeling of emptiness, a momentary lack of breath or sudden weakness, a fleeting sensation of fainting.

Depending on their origin, they can be distinguished into supraventricular and ventricular depending on the location of the focus that determines them.

The diagnosis is made with the electrocardiogram: the cardiologist raises the clinical suspicion that is confirmed when an abnormal heartbeat is recorded on the electrocardiogram, both standard and Holter (extended recording from 24 hours up to 7 and 15 days).

Are you looking for a therapeutic solution or do you want to book a consultation for your extrasystoles?

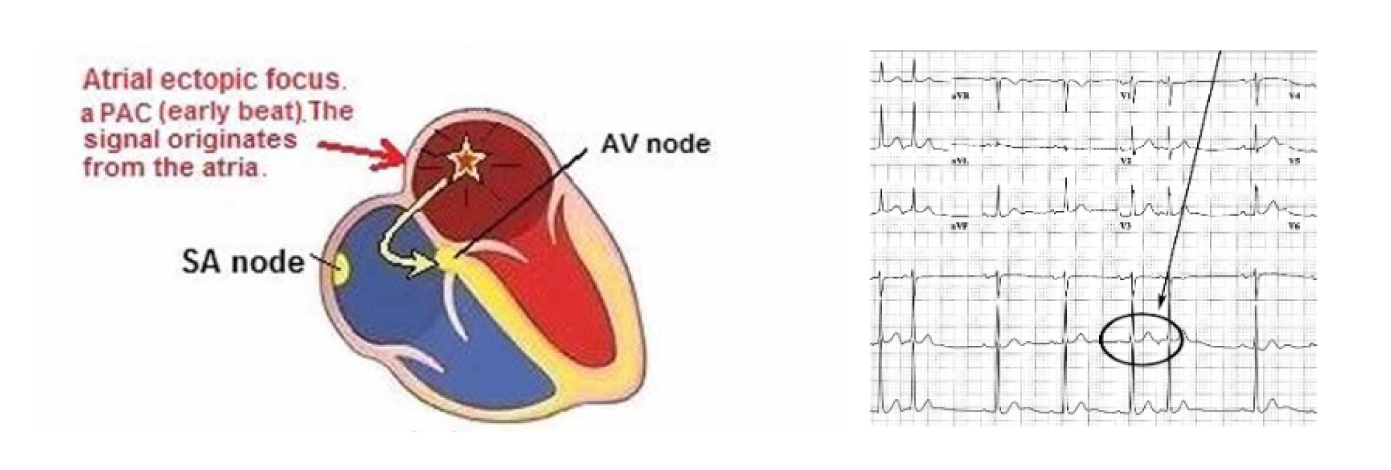

Supraventricular extrasystoles

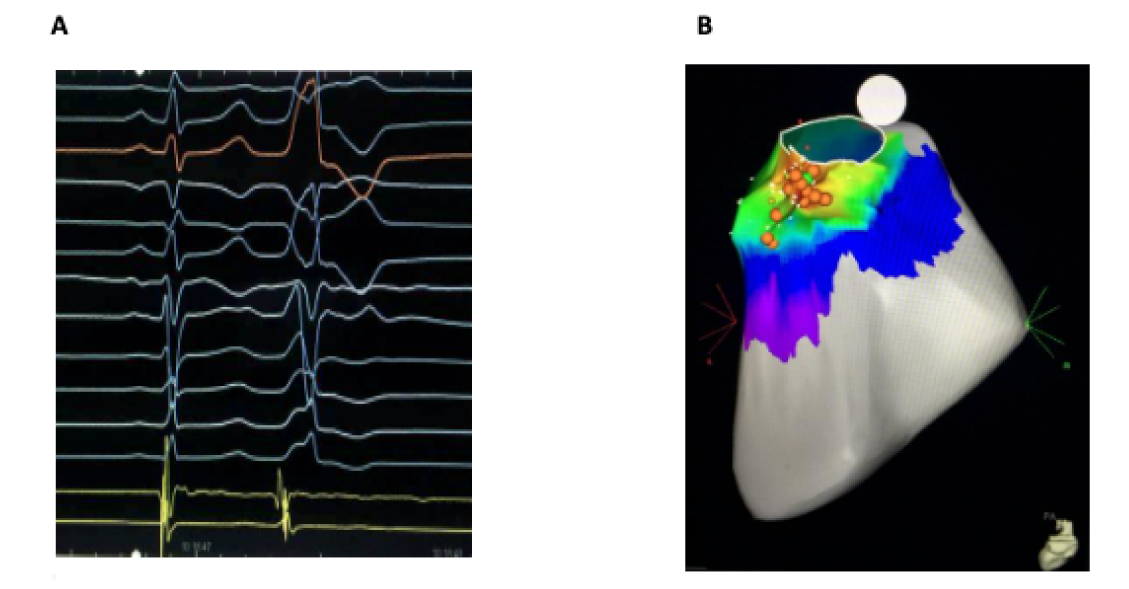

They originate from the atria or from the junction between the atria and ventricles (Fig 1). In general, this entails a lower risk. However, they can be symptomatic and in some cases trigger sustained supraventricular arrhythmias such as paroxysmal tachycardia and atrial fibrillation.

The treatment of supraventricular extrasystoles therefore depends on the symptoms they cause and their role in causing more serious arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

In case of need for treatment, the first level consists of antiarrhythmic therapy.

Where pharmacological treatment is not effective, not tolerated or not accepted by the patient, the next step is ablative therapy.

The patient undergoes electrophysiological study and electroanatomical mapping of the atrial chambers and once the source has been identified it is neutralized by CT ablation (Fig 2).

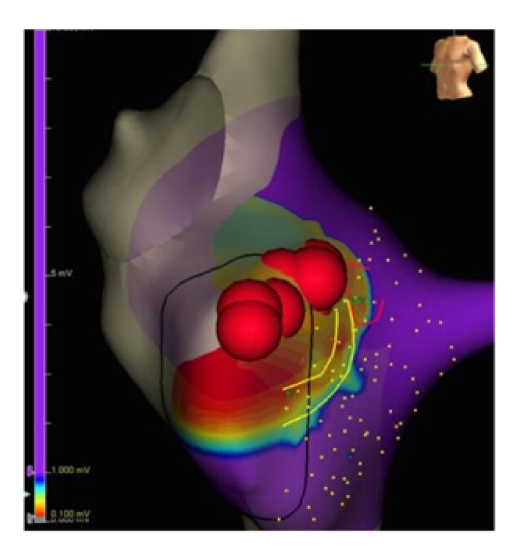

Ventricular extrasystoles

These originate from the ventricular cavities which constitute the actual pumps that push blood into the cardiovascular system.

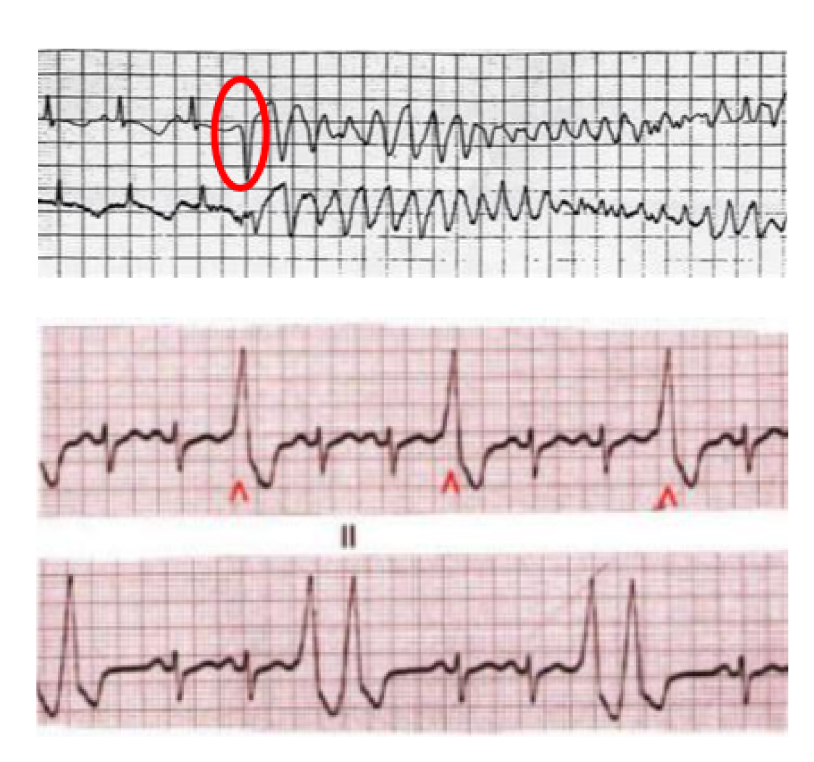

For this reason, arrhythmias that arise at this level are considered more important than those that originate from the atria (Fig 3).

Ventricular extrasystoles in healthy heart

Most ventricular extrasystoles are not dangerous, especially those that are not associated with concomitant heart disease. Ventricular extrasystoles in a normal heart very often originate from the part of the ventricles that goes towards the aorta (left ventricle) and the pulmonary artery (right ventricle), the latter being by far the most frequent. These are infundibular extrasystoles that are often symptomatic and bring the patient to the cardiologist even though they are not generally dangerous. The arrhythmologist, once identified, excludes the presence of an associated heart disease and decides on the treatment that will be applied only if they are very symptomatic or extremely numerous.

The first level of treatment is represented by the administration of antiarrhythmic drugs, the most commonly used of which are beta blockers. In case of ineffectiveness, intolerance or refusal of medical therapy, the patient is subjected to an electrophysiological study and electroanatomical mapping of the ventricular chambers and once the source focus has been identified, it is neutralized by CT ablation (Fig 4).

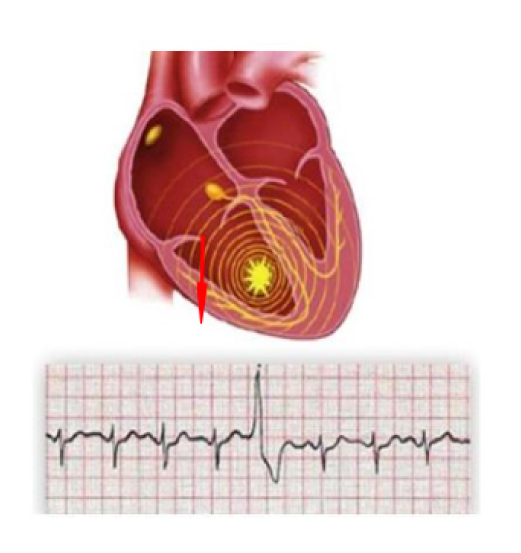

Ventricular extrasystoles in a diseased heart

In the presence of concomitant heart disease, the clinical significance of ventricular extrasystoles may differ, as in the case of structural or electrical cardiac abnormalities. Extrasystoles can act as a trigger for a rapid and prolonged arrhythmia, potentially causing severe symptoms and, in some cases, cardiac arrest (Fig. 5).

The cardiologist must determine the type of heart disease affecting the patient with ventricular extrasystole. On one hand, there are cardiopathies caused by disturbances in coronary circulation, such as myocardial infarction, heart diseases due to abnormalities of the heart valves, cardiopathies related to conditions affecting the cardiac muscle cells (cardiomyopathies), those caused by congenital heart malformations, and inflammatory conditions (myocarditis). On the other hand, there are primarily electrical heart diseases caused by abnormalities in the ion channels located on the membrane of cardiac cells. Such abnormalities, as seen in Brugada Syndrome, Long QT, Short QT, and catecholaminergic polymorphic tachycardia, lead to electrical instability in a heart that is morphologically and structurally normal.

The presence of very frequent forms, with multiple morphologies (polymorphic) and closely following the preceding heartbeat (premature), indicates a higher risk situation. In such cases, treatment will be necessary. The treatment will vary from case to case, depending on the underlying heart disease and the presentation of the extrasystoles.

It may involve the use of antiarrhythmic drugs and catheter ablation, combined in various ways depending on the patient's clinical condition. This is because the treatment for these patients must also address the underlying heart disease.

Are your extrasystoles frequent and worrying you?

Book a check-up consultation to rule out underlying pathologies.